- Joined

- Aug 15, 2012

- Bikes

- KTM 613 EXC, BMW R90S & Dakar, MZ250, Norton 16H, Honda - 500 Fs & Xs, DRZs, XLs XRs CRFs CT110s etc

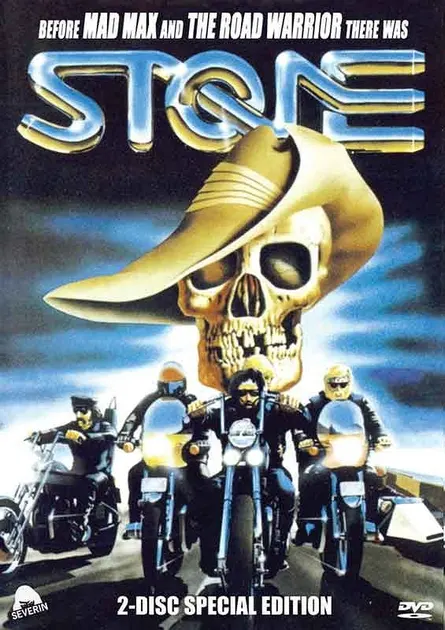

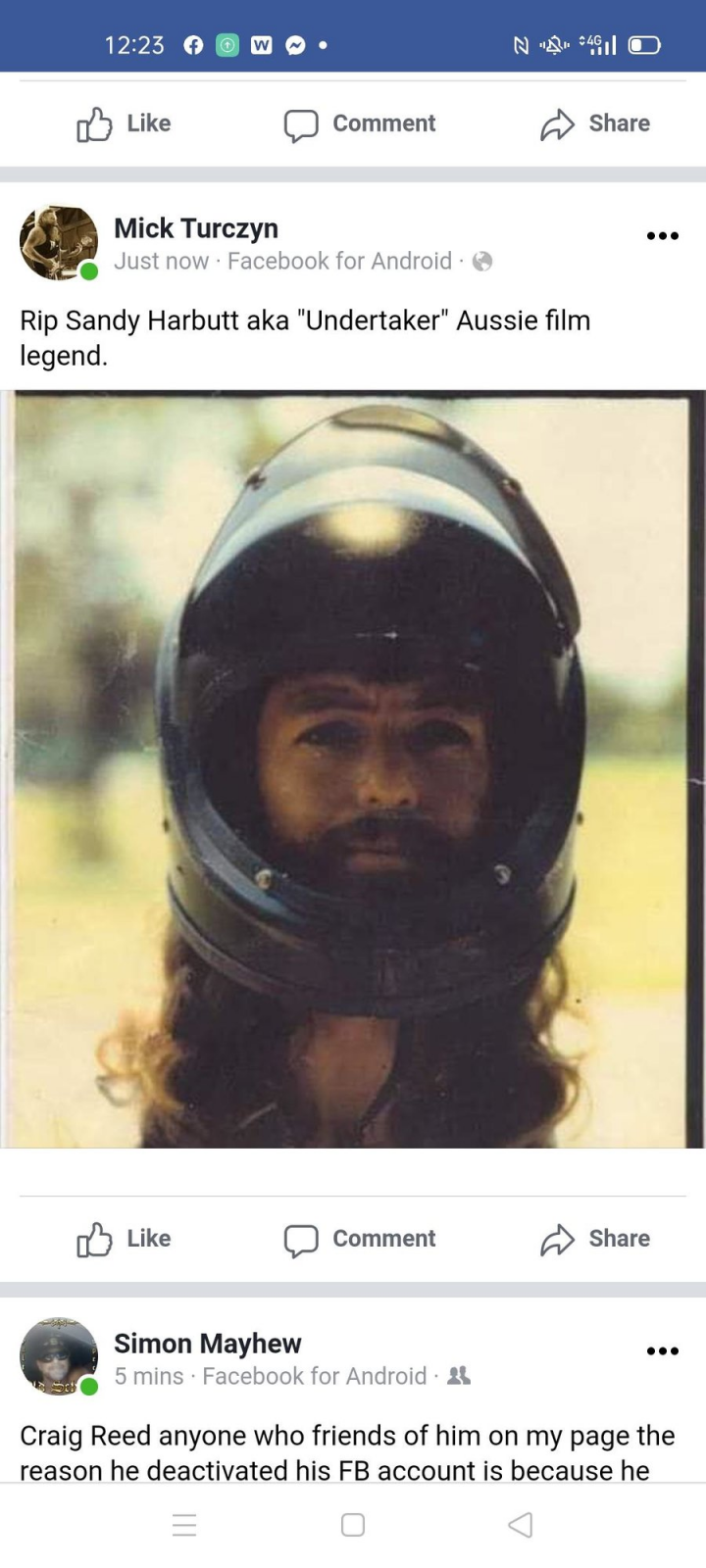

Sandy Harbutt (1941-2020), who died last Sunday was the driving force behind the Aussie movie Stone, from 1974.

I knew him back in the day, only on a nodding basis, as he then lived next door to my brother, in Neutral Bay, on a side lane to the road that was used for the race scene in the movie. Back then, he'd regularly be seen sitting in an old Riley sportscar, windows slightly cracked - smoke emanating.

We drag the movie out on occasion and show it - and will do so again tonight at the Ulysses Club Thailand meeting. I've got it running now. RIP Gravedigger.

Here's an old review of the movie by Tom O'Regan

Stone Review

In the late sixties and early seventies, Australia, with the rise of the Australian Film institute, with the formation various funding bodies, with the emergence of the various tax breaks set out to not only to revitalize and sustain our gradually re-emerging film industry, but to create a national cinema. Not just a film industry but also a cinema. An attempt to create something we can show the world, to put ourselves on the cultural map. We made films of the nature ‘Picnic at Hanging Rock’ (197*) and such like. We made our quality films and the rest of the world took notice. We did not merely want film, Australia was instead seeking high art.

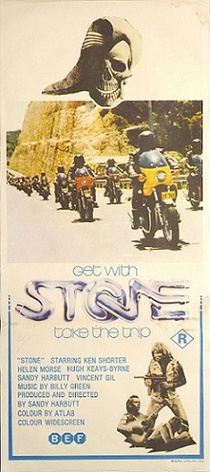

‘Stone’ (1974) was not one of these films. Stone was instead something else. It lived in the places of genre. The biker film, the mystery film, the exploitation film. This is where Stone dwells and perhaps why it is unacknowledged. Australia has not excelled, particularly, in the arena of the genre film. Apart from occasional excursions within the 80’s and 90’s, brought by the rise of large budget cinema in the 80’s and the rise of the more overtly quirky films of the later 90’s, we have been lacking in this department. Stone however, can be regarded s the unacknowledged bastard stepchild of the 70’s mode of ‘high cinema’, banging its oversized and malformed head against the water pipes of cinema’s attic in an effort to be heard.

The member of the Gravediggers, a gang of ex-Vietnam, veteran, Satanist bikers is being murdered after one of their number witnesses the assassination of a pro-environment politician who is directing protest against a new waterside development. Only sighting the bikers club insignia, the assassin is forced to hunt and kill the various members of the gang in the hope one of them will be the witness, including a moderately infamous decapitation by wire of a motorcyclist. Finally, police officer Stone is sent in, to go undercover amongst the bikers, where is reluctantly and the gradually accepted, in turn accepting their way of life and seeing it as, perhaps, a better way, becoming all but part of it, up to participating in a gang related brawl. Eventually, however, after a vicious battle between the assassin and the Gravediggers, he makes a choice to which world he belongs and stops the bikers from taking the life of their predator. Following this, while in his home, his musings of the nature of the bikers is interrupted by the Gravediggers, who come in and nearly or perhaps do, stomp him near to death, stripping him of his gang initiation earring and club jacket. The movie closes with his second choice of where he belongs when he tells his wife, as she rings the police, the words that close the movie, the oft repeated refrain of the Gravediggers “No Cops.”

What perhaps separated Stone from the films of the era was its nihilism. While the films of the era, such as ‘The Cars That Ate Paris’ and ‘Walkabout’ concentrated on the rejection of the values of middle class and ‘high’ society a and, indeed, even the seminal American biker movie ‘Easy rider’ merely rejected a part of society, Stone was against all of society, from the police, to big business, to the counterculture, to merely the normal life of Stone and his wife. All of it was rejected in favor of the only sustainable value in the movies eyes, the motor cycle club, which is shown to be close because of both what they have been through and also who they can trust. They accept the dispossessed into their ranks and reject everything else. Their rejection is the realization that the rest of society discarded them first, sent them off to Vietnam to die and

To continue this point, one of the central ideas of Australian cinema is the idea of lifestyle as a character, however exaggerated. The shearing of ‘Sunday too far away’, the coastal tourism lifestyle of ‘Muriel’s Wedding’, the seedy Kings Cross underworld of ‘Two Hands’. These all make the backdrop against they occur as important as the characters themselves, as integral to the story and it’s flavor as the dialogue. This is something that is also apparent in Stone. The biker lifestyle becomes the movie, the rules and attitudes become the central character, stuck in a kind of doom romance with Officer Stone, his vicious beating at the films finale the actions of a jilted lover as much as the bikers revenge. His rejection of the police as much a rejection of his wife and the values, the lifestyle, she represents as an acceptance of biker culture. This too is true. A character becomes a lifestyle as well.

However, for all this, the film itself is hardly a work of art. It has aged badly, it’s atavistic bikers resembling relatively harmless hippies more than anything, it’s once shocking violence becoming, except for the brutal final scene, relatively tame. This is perhaps were the exploitation genre fails. It relies on shock, it relies on titillation and once these are gone, there isn’t truly that much left to the film. While still entertaining, still interesting, much of the entertainment value now comes from mocking the performances, the presence of the epynomous Bill Hunter and so forth. Sadly, whatever Stone once was, now it has become a vaguely amusing joke.

There is, however, something special about what Sandy Harbutt did at the time. He became Australia’s first true Auteur. The film was entirely his vision, created from something he knew and sought to develop, writing the screenplay, directing in it, helping to perform the music and finally, acting within it. It was a film held together, more than anything, by a singular vision, something few other Auteur can truly claim. It was perhaps due to the climate of the seventies created by the Australian Film Commission that he was in fact able to do this, relying less on commercial or studio monies as otherwise might be the case, outside pressures that may cause a single vision to be compromised by many in the name of marketability, though, apparently, with limited funds, Harbutt had paid his camera crew and a sizable chunk of his cast in beer and pot.

Sandy Harbutt, however, has made nothing since, the only involvement in the Australian film industry he has had since was the chance to drive a truck, something he rejected so as not to deny a professional driver work. However, Stone experienced something of a revival at the hands of the Australian documentary ‘Stone Forever’ (1999), which explored the impact of the film both then and since, with a particular emphasis on biker culture. The screening of this, coupled with the movie, placed the film itself back on the Australian Film making map, as much due to the quality of the documentary, with many screenings filled with capacity, both with cinema aficionados and bikers.

In it’s own time, while immensely successful in the cinemas, Stone, like many classics of the exploitation genre, was even more of a hit at the drive in, something that is perhaps an entirely different cinematic culture. Perhaps the closest allegory to it’s performance, though Stone perhaps lacks the same level of memetic viral obsessive ness in it’s marketing and personal distribution as this particular contemporary, is the ‘Billy Jack’ series, which developed a broad audience through word of mouth, not a great deal like this having been produced in Australia before or since. Stone, upon it’s wider popularity being obtained, there were rumors that the film was apparently available in two prints, one containing the decapitation scene and the incidents of full frontal nudity and one without American Schlockmeister Russ Meyer.

For all it’s popularity and the endorsement of Australian radio personality John Laws, critics accepted the film less than warmly, regarding it, along with the like of The Adventures of Barry McKenzie (1972), as something of a cultural embarrassment, to be swept under the carpet. The Alvin Purples, the Barry McKenzie’s, the Stones. These are the forgotten parts of Australian film history, lacking the presentability of the films of Peter Weir or Baz Lurhman, but an important part none the less and one that perhaps should be acknowledged. It must be realized that, while the films themselves may not be particularly ‘important’ films, they are still /important/ films, Australia’s filmic underground and, in Stone’s case the stillborn career of someone who may have been great, the early hiccups and musings of a nascent film industry that has given us what we have today and this is why they must be remembered.

.............

Here's a nice story from the production side... a mad stunt

“Even If I Die, Don’t Cut the Shot…”

By John Hamilton on December 23, 2017 in Other

Peter Armstrong mid-flight at Lurline Bay, by Sandy Harbutt

A death-defying motorbike leap off an 80 foot cliff near Lurline Bay, as told by Stone Director Sandy Harbutt.

1974. It’s a sunny November morning and hundreds gather on the cliffs surrounding Lurline Bay. A timber ramp points precariously over a rocky precipice. Waves slap against the rocks 80 feet below. Peter Armstrong, career stuntman, sits leather-clad on his Honda 450. Helmet on, he waits.

Peter’s been kicked, punched, and thrown about more times than he can remember; hit front-on by cars at 70 kilometres per hour, rolling off the bonnet – no padding – then straight back up for another two takes. This might be his once-in-a-lifetime stunt, the one to be remembered by.

“Even if I die, don’t cut the shot,” he’d made the director promise.

All is silent. Peter revs his engine. The director calls, “Action!” Not quite Hollywood, this is the Australian cult cinema classic, Stone.

Directed by Sandy Harbutt, critics and bikers alike hailed Stone as the first honest portrayal of their lifestyle. A heady concoction of drugs, sex, guns, and action-fuelled drama; the film was like nothing Australian cinema had seen before. Harbutt also plays a lead role in the film, and co-authored the screenplay.

A huge fan of Stone, Tarantino hails Harbutt, “A true visionary, who has the goods, and delivers them with a tremendous amount of impact.”

Tarantino also credits Harbutt for directing “the most authentic and realistic ending of a biker movie in the history of film… when you see that shot, you’re like – oh my God, what a movie!”

In a rare interview, I caught up with Stone director Sandy Harbutt, who agreed to tell us more about stuntman Peter Armstrong’s legendary leap off Lurline Bay:

I’d written the motorbike jump into the script, but after looking at both sides of Sydney Heads, I couldn’t find a suitable cliff, so I told our stuntman (Peter Armstrong) we might have to postpone. About six weeks later, Peter came back saying he’d found a cliff, so off we went in his beloved Valiant Charger (chuckles) to Maroubra.

Standing close to the edge at that mighty height, I said, “So okay, where is it?” and he went, “Off here.” I said, “You gotta be kidding,” then he says, “No, I can do it.” “Not on my fucken movie!” I replied, and walked off.

But he followed. “Stop, no look sir, stop,” he kept saying. Peter was so professional he called me ‘Sir’, even though he was my best friend, because we were on the job.

So he drags me back and says, “We can have a ramp, I can get plenty of speed.” And I said, “There’s fucken rocks down there!” Then he says, “Look, Sandy, all my life I’ve been building to do a stunt like this. You’ve been building to make this picture. Give it to me. Give it to me!”

I feel like crying now, and his crazy, perfect blue eyes – I knew how brilliant he was, because he could do anything, this guy. And he was the toughest guy I ever met.

Anyhow, he eventually convinced me, and a crowd of about 100 lined the cliff on the day. I explained they all had to stay back until I called “Cut,” because it would otherwise ruin the camera work. Even I couldn’t look over until after the shot was done.

Peter tears at the ramp like a maniac and flies into mid-air. After seven long seconds I hear a humungous splash, call “Cut,” and look over the edge. And there he is, floating. He then sticks his arm up, and the crowd cheers. But this was actually just an unconscious twitch – Peter later told me he couldn’t remember it. So anyhow, he’d hit, went under, got the helmet off, and then somehow or other he surfaces, rolls onto his back, and is floating unconscious. Once he made it into that position he passed out (laughs). So when the rescuers got to him, he was asleep, and they had to fish him out. That was the worst moment of my life; I thought he was dead. But then he sat up and the crowd went wild.

The boat then sped off to Coogee, where an Ambulance was waiting, while I burnt back on my bike. By then they were landing the boat (laughs and sighs). Oh dear, and there he was – there he was – barely able to walk. He’d taken a full-body impact, just like a punch to every part of your body. He’d hit the water at God knows what speed, but he could still stand. Just. So I walked over and hugged him (laughs). And the world’s humblest man, he says, “We did it.” “No, we didn’t do it,” I said, “you did it, Peter!”

I knew him back in the day, only on a nodding basis, as he then lived next door to my brother, in Neutral Bay, on a side lane to the road that was used for the race scene in the movie. Back then, he'd regularly be seen sitting in an old Riley sportscar, windows slightly cracked - smoke emanating.

We drag the movie out on occasion and show it - and will do so again tonight at the Ulysses Club Thailand meeting. I've got it running now. RIP Gravedigger.

Here's an old review of the movie by Tom O'Regan

Stone Review

In the late sixties and early seventies, Australia, with the rise of the Australian Film institute, with the formation various funding bodies, with the emergence of the various tax breaks set out to not only to revitalize and sustain our gradually re-emerging film industry, but to create a national cinema. Not just a film industry but also a cinema. An attempt to create something we can show the world, to put ourselves on the cultural map. We made films of the nature ‘Picnic at Hanging Rock’ (197*) and such like. We made our quality films and the rest of the world took notice. We did not merely want film, Australia was instead seeking high art.

‘Stone’ (1974) was not one of these films. Stone was instead something else. It lived in the places of genre. The biker film, the mystery film, the exploitation film. This is where Stone dwells and perhaps why it is unacknowledged. Australia has not excelled, particularly, in the arena of the genre film. Apart from occasional excursions within the 80’s and 90’s, brought by the rise of large budget cinema in the 80’s and the rise of the more overtly quirky films of the later 90’s, we have been lacking in this department. Stone however, can be regarded s the unacknowledged bastard stepchild of the 70’s mode of ‘high cinema’, banging its oversized and malformed head against the water pipes of cinema’s attic in an effort to be heard.

The member of the Gravediggers, a gang of ex-Vietnam, veteran, Satanist bikers is being murdered after one of their number witnesses the assassination of a pro-environment politician who is directing protest against a new waterside development. Only sighting the bikers club insignia, the assassin is forced to hunt and kill the various members of the gang in the hope one of them will be the witness, including a moderately infamous decapitation by wire of a motorcyclist. Finally, police officer Stone is sent in, to go undercover amongst the bikers, where is reluctantly and the gradually accepted, in turn accepting their way of life and seeing it as, perhaps, a better way, becoming all but part of it, up to participating in a gang related brawl. Eventually, however, after a vicious battle between the assassin and the Gravediggers, he makes a choice to which world he belongs and stops the bikers from taking the life of their predator. Following this, while in his home, his musings of the nature of the bikers is interrupted by the Gravediggers, who come in and nearly or perhaps do, stomp him near to death, stripping him of his gang initiation earring and club jacket. The movie closes with his second choice of where he belongs when he tells his wife, as she rings the police, the words that close the movie, the oft repeated refrain of the Gravediggers “No Cops.”

What perhaps separated Stone from the films of the era was its nihilism. While the films of the era, such as ‘The Cars That Ate Paris’ and ‘Walkabout’ concentrated on the rejection of the values of middle class and ‘high’ society a and, indeed, even the seminal American biker movie ‘Easy rider’ merely rejected a part of society, Stone was against all of society, from the police, to big business, to the counterculture, to merely the normal life of Stone and his wife. All of it was rejected in favor of the only sustainable value in the movies eyes, the motor cycle club, which is shown to be close because of both what they have been through and also who they can trust. They accept the dispossessed into their ranks and reject everything else. Their rejection is the realization that the rest of society discarded them first, sent them off to Vietnam to die and

To continue this point, one of the central ideas of Australian cinema is the idea of lifestyle as a character, however exaggerated. The shearing of ‘Sunday too far away’, the coastal tourism lifestyle of ‘Muriel’s Wedding’, the seedy Kings Cross underworld of ‘Two Hands’. These all make the backdrop against they occur as important as the characters themselves, as integral to the story and it’s flavor as the dialogue. This is something that is also apparent in Stone. The biker lifestyle becomes the movie, the rules and attitudes become the central character, stuck in a kind of doom romance with Officer Stone, his vicious beating at the films finale the actions of a jilted lover as much as the bikers revenge. His rejection of the police as much a rejection of his wife and the values, the lifestyle, she represents as an acceptance of biker culture. This too is true. A character becomes a lifestyle as well.

However, for all this, the film itself is hardly a work of art. It has aged badly, it’s atavistic bikers resembling relatively harmless hippies more than anything, it’s once shocking violence becoming, except for the brutal final scene, relatively tame. This is perhaps were the exploitation genre fails. It relies on shock, it relies on titillation and once these are gone, there isn’t truly that much left to the film. While still entertaining, still interesting, much of the entertainment value now comes from mocking the performances, the presence of the epynomous Bill Hunter and so forth. Sadly, whatever Stone once was, now it has become a vaguely amusing joke.

There is, however, something special about what Sandy Harbutt did at the time. He became Australia’s first true Auteur. The film was entirely his vision, created from something he knew and sought to develop, writing the screenplay, directing in it, helping to perform the music and finally, acting within it. It was a film held together, more than anything, by a singular vision, something few other Auteur can truly claim. It was perhaps due to the climate of the seventies created by the Australian Film Commission that he was in fact able to do this, relying less on commercial or studio monies as otherwise might be the case, outside pressures that may cause a single vision to be compromised by many in the name of marketability, though, apparently, with limited funds, Harbutt had paid his camera crew and a sizable chunk of his cast in beer and pot.

Sandy Harbutt, however, has made nothing since, the only involvement in the Australian film industry he has had since was the chance to drive a truck, something he rejected so as not to deny a professional driver work. However, Stone experienced something of a revival at the hands of the Australian documentary ‘Stone Forever’ (1999), which explored the impact of the film both then and since, with a particular emphasis on biker culture. The screening of this, coupled with the movie, placed the film itself back on the Australian Film making map, as much due to the quality of the documentary, with many screenings filled with capacity, both with cinema aficionados and bikers.

In it’s own time, while immensely successful in the cinemas, Stone, like many classics of the exploitation genre, was even more of a hit at the drive in, something that is perhaps an entirely different cinematic culture. Perhaps the closest allegory to it’s performance, though Stone perhaps lacks the same level of memetic viral obsessive ness in it’s marketing and personal distribution as this particular contemporary, is the ‘Billy Jack’ series, which developed a broad audience through word of mouth, not a great deal like this having been produced in Australia before or since. Stone, upon it’s wider popularity being obtained, there were rumors that the film was apparently available in two prints, one containing the decapitation scene and the incidents of full frontal nudity and one without American Schlockmeister Russ Meyer.

For all it’s popularity and the endorsement of Australian radio personality John Laws, critics accepted the film less than warmly, regarding it, along with the like of The Adventures of Barry McKenzie (1972), as something of a cultural embarrassment, to be swept under the carpet. The Alvin Purples, the Barry McKenzie’s, the Stones. These are the forgotten parts of Australian film history, lacking the presentability of the films of Peter Weir or Baz Lurhman, but an important part none the less and one that perhaps should be acknowledged. It must be realized that, while the films themselves may not be particularly ‘important’ films, they are still /important/ films, Australia’s filmic underground and, in Stone’s case the stillborn career of someone who may have been great, the early hiccups and musings of a nascent film industry that has given us what we have today and this is why they must be remembered.

.............

Here's a nice story from the production side... a mad stunt

“Even If I Die, Don’t Cut the Shot…”

By John Hamilton on December 23, 2017 in Other

Peter Armstrong mid-flight at Lurline Bay, by Sandy Harbutt

A death-defying motorbike leap off an 80 foot cliff near Lurline Bay, as told by Stone Director Sandy Harbutt.

1974. It’s a sunny November morning and hundreds gather on the cliffs surrounding Lurline Bay. A timber ramp points precariously over a rocky precipice. Waves slap against the rocks 80 feet below. Peter Armstrong, career stuntman, sits leather-clad on his Honda 450. Helmet on, he waits.

Peter’s been kicked, punched, and thrown about more times than he can remember; hit front-on by cars at 70 kilometres per hour, rolling off the bonnet – no padding – then straight back up for another two takes. This might be his once-in-a-lifetime stunt, the one to be remembered by.

“Even if I die, don’t cut the shot,” he’d made the director promise.

All is silent. Peter revs his engine. The director calls, “Action!” Not quite Hollywood, this is the Australian cult cinema classic, Stone.

Directed by Sandy Harbutt, critics and bikers alike hailed Stone as the first honest portrayal of their lifestyle. A heady concoction of drugs, sex, guns, and action-fuelled drama; the film was like nothing Australian cinema had seen before. Harbutt also plays a lead role in the film, and co-authored the screenplay.

A huge fan of Stone, Tarantino hails Harbutt, “A true visionary, who has the goods, and delivers them with a tremendous amount of impact.”

Tarantino also credits Harbutt for directing “the most authentic and realistic ending of a biker movie in the history of film… when you see that shot, you’re like – oh my God, what a movie!”

In a rare interview, I caught up with Stone director Sandy Harbutt, who agreed to tell us more about stuntman Peter Armstrong’s legendary leap off Lurline Bay:

I’d written the motorbike jump into the script, but after looking at both sides of Sydney Heads, I couldn’t find a suitable cliff, so I told our stuntman (Peter Armstrong) we might have to postpone. About six weeks later, Peter came back saying he’d found a cliff, so off we went in his beloved Valiant Charger (chuckles) to Maroubra.

Standing close to the edge at that mighty height, I said, “So okay, where is it?” and he went, “Off here.” I said, “You gotta be kidding,” then he says, “No, I can do it.” “Not on my fucken movie!” I replied, and walked off.

But he followed. “Stop, no look sir, stop,” he kept saying. Peter was so professional he called me ‘Sir’, even though he was my best friend, because we were on the job.

So he drags me back and says, “We can have a ramp, I can get plenty of speed.” And I said, “There’s fucken rocks down there!” Then he says, “Look, Sandy, all my life I’ve been building to do a stunt like this. You’ve been building to make this picture. Give it to me. Give it to me!”

I feel like crying now, and his crazy, perfect blue eyes – I knew how brilliant he was, because he could do anything, this guy. And he was the toughest guy I ever met.

Anyhow, he eventually convinced me, and a crowd of about 100 lined the cliff on the day. I explained they all had to stay back until I called “Cut,” because it would otherwise ruin the camera work. Even I couldn’t look over until after the shot was done.

Peter tears at the ramp like a maniac and flies into mid-air. After seven long seconds I hear a humungous splash, call “Cut,” and look over the edge. And there he is, floating. He then sticks his arm up, and the crowd cheers. But this was actually just an unconscious twitch – Peter later told me he couldn’t remember it. So anyhow, he’d hit, went under, got the helmet off, and then somehow or other he surfaces, rolls onto his back, and is floating unconscious. Once he made it into that position he passed out (laughs). So when the rescuers got to him, he was asleep, and they had to fish him out. That was the worst moment of my life; I thought he was dead. But then he sat up and the crowd went wild.

The boat then sped off to Coogee, where an Ambulance was waiting, while I burnt back on my bike. By then they were landing the boat (laughs and sighs). Oh dear, and there he was – there he was – barely able to walk. He’d taken a full-body impact, just like a punch to every part of your body. He’d hit the water at God knows what speed, but he could still stand. Just. So I walked over and hugged him (laughs). And the world’s humblest man, he says, “We did it.” “No, we didn’t do it,” I said, “you did it, Peter!”