Some interesting information on the situation with the Hmong in Xaisomboun Special Zone (south of Phonsavan) in the link below:

http://members.ozemail.com.au/~yeulee/Topical/Hmong%20rebellion%20in%20Laos.html

Some extracts here:

Introduction

On the 4[SUP]th[/SUP] of June 2005, a group of 171 people (20 Hmong and 9 Khmu families with 83 adults and 88 children) emerged from the forest and put themselves in the hands of a government police officer in the Saisomboun Special Zone, north of Vientiane province. Their arrival had been well publicised as one of the few rebel groups that voluntarily surrendered. Government troops of the Lao People's Democratic Republic (Lao PDR) and other officials were soon on the scene, including four US citizens from the Fact Finding Commission, a lobby group based in California, USA. The US visitors were there to witness the rallying and to ensure that the group was given all the help they needed after spending 30 years in the jungle of central Laos refusing to be part of the Lao communist regime. The Americans were promptly arrested for "liaising illegally" with the Hmong, but were released and deported a few days later after diplomatic discussion between the two countries (BBC News, World Edition, 7 June 2005).

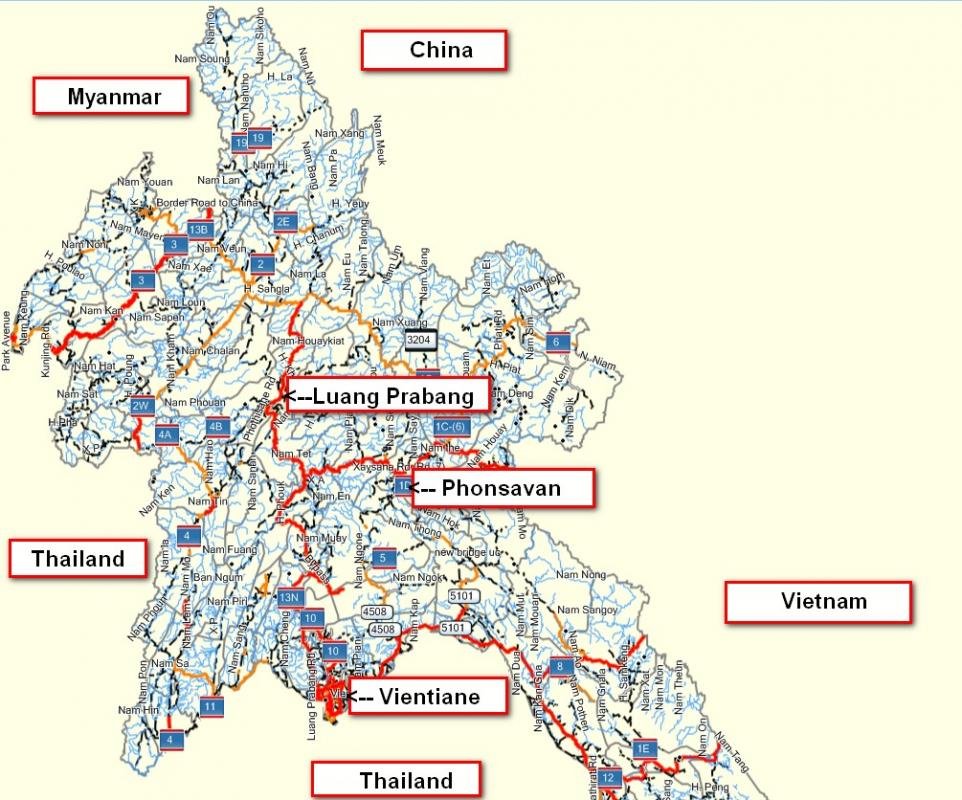

The new arrivals were taken a few hours later by military trucks to Phu Kout in Xieng Khouang province where they were allocated 50 hectares of farm land and other forms of emergency assistance, with local officials welcoming them "as a gesture of appreciation for their support to (sic) the government's policy of alleviating poverty", according to Vientiane Times, the official English language newspaper (http://www.vientianetimes.org.la/Contents/2005-107/Phou.htm). For the Lao authorities, the Hmong families coming out of the jungle were no more than villagers on the move in search of new farming land. There was no question of rebellion or resistance.

On the other side of the globe, however, the U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan, on 7 June 2005 in New York, welcomed reports on the humane treatment extended to "Hmong, coming out of remote areas of Laos" and urged the Vientiane government to continue providing the necessary assistance to them in case a larger number decide to follow in the days ahead. The Secretary-General said the UN was ready to provide every kind of humanitarian assistance to such groups the Lao government may request (News Updated, Tuesday 12 July 2005 at http://news.webindia123.com/news/showdetails.asp?id=86608&cat=World). This is the first time, the UN made any public acknowledgement of the existence of Hmong rebels in Laos.

Meanwhile, a television report in France entitled "The Secret War in Laos" was broadcast on 16 June 2005 on France Channel 2 (http://info.france2.fr/emissions/73095-fr.php). It shows a campaign of "ferocious repression, even extermination" conducted for the last three decades by the leaders of the one-party state of the Lao PDR against thousands of Hmong in the jungle of Saisomboun and Bolikhamsay province (Lao Movement for Human Rights, "Petition to Save the Hmong in Saisomboun" at http://www.mldh-lao.org/petition_online/petition1.php). A Lao Foreign Ministry spokesman, Mr Yong Chanthalansy, dismissed the televised report as an attempt to "make something out of nothing", claiming that there were no rebels in Laos and that the two French reporters had been mislead by "bad people" ("khaun-bordi") to invent the report (Lao Language Program, Radio Free Asia, 26 June 2005).

Ever since 1975 when the communist Pathet Lao (Lao Nation) gained control of Laos with the support of the then Soviet Union and North Vietnam, reports have continued to circulate about the exploits and suffering of many thousands of Hmong resistance fighters in remote jungles of that country. Initially they saw themselves as part of a rather ill-coordinated liberation movement to bring back democracy and non-communist rule to the country. After many years with little progress, this mission was changed in the last five years to one where the few small groups who remain, are simply fighting for survival as remnants of the so-called "secret army" which the American Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) recruited and supported during the Lao civil war from 1961 to 1973 (Conboy, 1995 and Warner, 1998). They now see their plight as the legacy of their involvement as members or descendants of the members of this CIA "secret army" and are thus targeted for extermination by the new communist regime.

This paper will focus on the Hmong and their armed resistance in Laos. It will begin with a short overview of the Hmong and their past armed rebellions. I will then discuss the current situation by looking at the internal and external factors and groups involved, before concluding on what will be the likely future of Hmong armed resistance in that country. In a sense, the Hmong cannot be said to be rebels against the Lao PDR government, as these dissidents have never joined the new regime and raise up against it from within its own ranks. Rather, they have chosen to resist the new communist rule by being fiercely anti-communist and by isolating themselves in their mountain fastnesses, refusing to be under the control of the new authorities.

Why the Hmong?

During the sixty-one years (1893-1954) of French colonial control of Laos, a number of armed rebellions by ethnic Khmu and Hmong minorities took place (Gunn, 1990). However, the Hmong remain today the only ones involved in armed resistance against the ruling authorities, although there are more than 40 other minorities living in the country. To explore the reason for this occurrence, we need to look at the role the Hmong have played in recent Lao history, and mythical religious beliefs which shape their political outlook and which influence them to instigate or join armed insurgency.

The Hmong began migrating from southern China to Laos during the last half of the 19th century, partly pushed by the Chinese Taiping Rebellions but largely in search of new farming lands. They settled in increasing numbers in Samneua, Phong Saly, Luang Prabang and Xieng Khouang provinces. After Laos became a French colony in 1893, they became subjected to heavy taxes: a resident tax paid to the local Lao chiefs and a colonial tax for the French administrators. This official tax burden soon lead Hmong leaders to organise an ambush against tax collectors in 1896 at Ban Khang Phanieng in Muong Kham, Xieng Khouang province (Yang Dao, 1975: 46). The French were concerned enough to agree to negotiate with the recalcitrant Hmong, resulting in the establishment of Hmong Tasseng (or canton chief) positions that were accountable directly to the French authorities.

The first Hmong Tasseng was given to the chief negotiator, Kiatong Mua Yong Kai (Muas Zoov Kaim) in Nong Het, and a second Tasseng was created near Xieng Khouang town for Ya Yang Her (Zam Yaj Hawj). This new arrangement would allow Hmong leaders to collect taxes from their own people and to have autonomy at the level of village administration, thus bypassing Lao officials at the Tasseng and Muong (or district) levels (Savina, 1924: 238). This was to affect greatly later Hmong involvement in the political events of Laos, for it gave the Hmong leadership a tendency to prefer dealing directly with Western allies (be them French or Americans) instead of the Lao, primarily because of a basic distrust of Lao officialdom based on these early confrontations. It also created a political outlook that would subsequently make some Hmong unwilling to accept orders directly from the Lao authorities.

These early administrative arrangements with the French brought relative calm to their relations with the Hmong until the latter took up arms again with the Pachai (Batchai) Vue messianic revolt from 1918 to 1921. This was to be the first of many revivalist cults that eventually gave rise to the "Chao Fa" or Lord of the Sky resistance in Laos today. A Hmong living in Tonkin (North Vietnam), Pachai was called upon to lead the rebellion out of a mythical belief that God had ordained him to deliver justice to his people who greatly suffered in the hands of Thai Dam (Black Thai) mandarins who not only conscripted Hmong men from their highland villages to work as free labour in lowland Thai Dam settlements but also levied opium tax on the Hmong.

However, the uprising soon included other grievances when French soldiers became involved in putting it down. Pachai fled Tonkin and sought refuge in Laos where he attracted a larger group of followers who saw in him the messiah they had been waiting for. It was claimed that the rebellion at its peak covered a territory of 40,000 square kilometres, spanning from Dien Bien Phu in Vietnam to Nam Ou in Luang Prabang and down to central Laos as far as Muong Cha (now renamed Saisomboun, the site of the current Hmong rebellion). Many Hmong took up arms with Pachai either out of their own personal grievances against lowlanders or in the fervent belief that they were part of a holy war foretold in many of their myths to regain the country they had lost long ago. In China, the Hmong had staged many such bloody uprisings through the centuries against Han Chinese domination based on a belief in the coming of a mythical king and a new Hmong kingdom (Tapp, 1982: 114-127).

When the Pachai rebellion spread to Laos, the largest military expedition ever organised by the French "by that date was mounted to break Batchai's rebellion; four companies of tirailleurs were brought in from other parts of Indochina to restore order." (Gunn, 1986: 115). Pachai was eventually tracked down and killed in his hide-out in Muong Heup, Luang Prabang, on 17 November 1921 (Le Boulanger, 1969: 360). Following his death, many Hmong rebel leaders who surrendered were decapitated at Nong Het by the French in front of Hmong spectators who were forced to assemble there. Other supporters of the revolt had to pay compensation to the French at fifty piastres "for every Lao or Vietnamese (soldiers) killed, not including compensation for loss of houses, cattle and crops" (Gunn, op cit.: 120).

From these early dissident experiences, the Hmong gravitated to full participation in the Lao struggle for independence from France (1945-1953) and the subsequent Lao civil war (1954- 1975) while other ethnic minorities remain very much in the background due to their smaller numbers or their lack of political participation in Lao national affairs. For the Hmong, however, political rivalry in Nong Het, Xieng Khouang, for the position of the local Tasseng chief made the Lo and Ly clans into bitter enemies when the French gave it to Touby Lyfoung in 1939 a few years after the death of Lo Bliayoa, the local kiatong chief (Chongtoua, 1998: 54). Touby Lyfoung thereafter remained faithful to the French and their right-wing Royal Lao Government (RLG) until his death in a communist political re-education camp in 1978.

During Japan's occupation of Laos in 1945, Faydang, one of Lo Bliayao's sons and Touby's political rival, sided with the Lao Issara (Free Lao) Movement. The Lao Issara, later known as the Pathet Lao (PL or Lao Homeland), urged on initially by the Japanese and later aided by North Vietnam and the Soviet Union, eventually won the fight for control of Laos in 1975 from the RLG, its America-supported faction in the civil war. The left-wing PL depended much on Faydang's Hmong and other hill tribes as its main support base in the jungles of north-eastern Laos. According to Stuart-Fox (1997: 79-80), the movement relied on ethnic minorities because it had "little opportunity to mobilise lowland Lao" people who were firmly under RLG control.

Prior to Laos being independent from France in 1954, those Hmong who sided with Touby Lyfoung were serving the French as right-wing village militia and French colonial soldiers. After the France left Indochina, the USA stepped in to counter the spread of communism (Freedman, 2002). Like the French, the Americans continued to see the Hmong as a trustworthy source of support. The French helped set up the RLG and its army which included many Hmong recruits. Among the latter was a young officer named Vang Pao who subsequently became a General and the Commander of the Second Military Region for the RLG in north-eastern Laos, the home of the Hmong and the seat of many major battles in the war.

In 1961, Vang Pao was offered support from the American CIA to set up the so-called "secret army" to combat the advances of PL troops. According to Prados (2003: 165), "in 1964 the Hmong secret army stood at 19,000 troops, building toward a strength of 23,000… The Hmong not only increased in number, but they also benefited from a constant stream of SGUs (special guerrilla units) sent to Thailand for advanced training… [and].. given heavier U.S. weapons". Known as Project Momentum by the CIA, this military support was to last until the Paris Cease-fire Agreement in 1973, leading to the dislocation and death of more than ten per cent of the estimated 300,000 Hmong involved in both sides of the war in Laos at the time.

Conclusion

The Lao PDR government has tried hard to blame the political instability in Laos on overseas Hmong, not local Hmong inside Laos whose dissidents have so far been officially labelled only as "bandits". It has tried quietly to solve the problem of local Hmong resistance in the backwaters of its jungles in northern Laos. It has tried to deny that such resistance groups exist rather than acknowledging them for what they are. It has made prominent reference in the country's Constitution to ethnic minorities as inseparable groups in the make-up of the Lao nation's unity who are accorded equal rights and obligations. It established the Saisomboun Special Zone as a show-case development site for the Hmong to attract Hmong rebels. There are now Hmong district and provincial governors, Hmong deputies in the National Assembly and even two Hmong Ministers (one as Minister for rural development and one as Minister for Justice) in the 2008 Lao government. Many Hmong are now in middle management in the Lao public service, more than under the old right-wing Royal Lao Government. A group of Lao soldiers who arrested and killed a number of Hmong civilians in 2002 in Saisomboun were reportedly executed by their local commander in front of survivors as an example of what is not allowed by the Lao government.

Apart from political differences, there seems to be other equally important factors involved in the equation, including racial discrimination of ethnic minorities by private Lao citizens, poverty and high inflation, ripe official graft and corruption, lack of economic and employment opportunities leading people to be easily susceptible to alternative political propaganda, resentment for lack of promotion and forced retirement of Hmong communist party supporters, alleged framing of Hmong officials for drug trafficking and other crimes leading to their arrests and imprisonment to deprive the Hmong of their leadership, murder and mysterious disappearances of repatriated Hmong refugee leaders and resistance leaders who rallied to the Lao PDR government.

These factors, together with free-for-all political propaganda (by word of mouth or radio broadcast) and material support from the diaspora Hmong outside Laos, will continue to make it difficult for the Hmong resistance fighters to stop their activities and for the Lao government to pacify them. This is now especially the case when the issue has been well played into the hands of the United Nations, the world media and international human rights organisations which have been keeping a close watch on anything to do with the Hmong and human rights abuses in Laos.

Regardless of this continuing impasse between the Lao government and the Hmong resistance movement, we need to keep the problem in perspective. There are currently 460,000 Hmong living in Laos according to the 2005 Lao government census. Of this number, less than 1,000 are now actively involved in the resistance, and their number ebbs and flows according to their fortune and the action of the Lao government at any particular time. The number may be small, but the Lao authorities will need to resolve many of the causes of this discontent. The problem is real and cannot be ignored or simply stemmed out by force as there are many underlying social, political and economic factors involved, not just ideological differences. So long as these needs are not addressed, even if existing insurgent groups are stemmed out, new ones will rise up to show their displeasure in one form or another. Resettlement as has been done in Muong Kao (Bolikhamsay province), Saisomboun and Muong Mok (Xieng Khouang) is a constructive and peaceful response to the problem, and is indicative of a cool and clear-headed approach. The government should be commended for stopping its previous use of armed retaliations and turning to rural development instead. This is the only way that will promote cooperation and trust between those involved in this long-standing conflict.